StatsCan released a pretty unimpressive trade balance report on Wednesday, showing the country swinging to a $638-million trade deficit in April, from a trade surplus of $766 million the month before.

These monthly numbers are pretty volatile and could easily reverse themselves next month, so we can’t read too much into them. But BMO chief economist Doug Porter decided to look at the long-term picture going back a few decades.

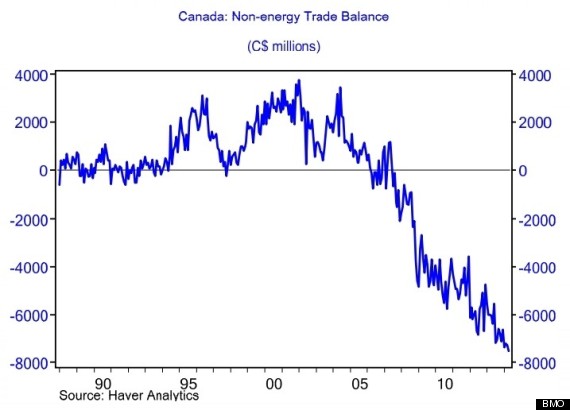

He separated the numbers for the energy sector from everything non-energy, and what he found is downright scary:

![bmo exports chart]()

Exports of non-energy goods have been on a downward swing for more than a decade, and hit an all-time low in the latest StatsCan report. As recently as 2006, we were selling more non-energy goods than we were buying, but that changed during the Great Recession and it hasn’t changed back.

This wouldn’t be a problem if energy exports could make up the difference. But, with about 8 per cent of Canada’s economy, the oil, gas and mining sector is hardly enough.

This is bad news in the short term and in the long term. In the short term, it means Canada’s economy could have a hard time finding sources of growth for the next while.

Story continues below

Canada’s post-recession recovery relied largely on consumers spending more, thanks to super-low interest rates. But consumer spending is slowing as debt burdens grow, and with it, retail, housing and other sectors directly dependent on the consumer dollar.

Economists say that’s OK, because the U.S. is recovering, and we can expect a jump in exports to pick up the slack from consumers. But uh oh, this long-awaited “great rotation” to exports isn’t happening.

“Better U.S. growth is expected to boost non-energy exports and start narrowing this deficit, but we’re not there yet,” Porter writes.

Then there are long-term problems. Bringing back the manufacturing capacity Canada has lost in recent years can’t be done overnight. The lower loonie “will help, but it won’t do miracles,” Desjardins economist Jimmy Jean said recently. That’s because Canada is now competing with developing economies for export-led jobs in manufacturing.

"The global manufacturing industry is more competitive than the 1990s, when Canadian factories benefited from a weakening dollar and the new North American Free Trade Agreement, which helped push manufacturing’s share of the economy to near the highest levels since the 1950s,” Bloomberg noted in a recent report on Ontario manufacturing.

So where Canada’s economic growth will come from in the months and years to come is a pretty tough question to answer. We can hope the housing market somehow, miraculously, keeps booming forever and consumer demand just keeps growing. But with weak income growth and massive energy bills facing consumers, that's unlikely.

And then we can hope for an even lower loonie, which is apparently what Porter is doing. “Maybe it’s not weak enough yet,” he mused.

These monthly numbers are pretty volatile and could easily reverse themselves next month, so we can’t read too much into them. But BMO chief economist Doug Porter decided to look at the long-term picture going back a few decades.

He separated the numbers for the energy sector from everything non-energy, and what he found is downright scary:

Exports of non-energy goods have been on a downward swing for more than a decade, and hit an all-time low in the latest StatsCan report. As recently as 2006, we were selling more non-energy goods than we were buying, but that changed during the Great Recession and it hasn’t changed back.

This wouldn’t be a problem if energy exports could make up the difference. But, with about 8 per cent of Canada’s economy, the oil, gas and mining sector is hardly enough.

This is bad news in the short term and in the long term. In the short term, it means Canada’s economy could have a hard time finding sources of growth for the next while.

Story continues below

Canada’s post-recession recovery relied largely on consumers spending more, thanks to super-low interest rates. But consumer spending is slowing as debt burdens grow, and with it, retail, housing and other sectors directly dependent on the consumer dollar.

Economists say that’s OK, because the U.S. is recovering, and we can expect a jump in exports to pick up the slack from consumers. But uh oh, this long-awaited “great rotation” to exports isn’t happening.

“Better U.S. growth is expected to boost non-energy exports and start narrowing this deficit, but we’re not there yet,” Porter writes.

Then there are long-term problems. Bringing back the manufacturing capacity Canada has lost in recent years can’t be done overnight. The lower loonie “will help, but it won’t do miracles,” Desjardins economist Jimmy Jean said recently. That’s because Canada is now competing with developing economies for export-led jobs in manufacturing.

"The global manufacturing industry is more competitive than the 1990s, when Canadian factories benefited from a weakening dollar and the new North American Free Trade Agreement, which helped push manufacturing’s share of the economy to near the highest levels since the 1950s,” Bloomberg noted in a recent report on Ontario manufacturing.

So where Canada’s economic growth will come from in the months and years to come is a pretty tough question to answer. We can hope the housing market somehow, miraculously, keeps booming forever and consumer demand just keeps growing. But with weak income growth and massive energy bills facing consumers, that's unlikely.

And then we can hope for an even lower loonie, which is apparently what Porter is doing. “Maybe it’s not weak enough yet,” he mused.