As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said this week he "misspoke" when predicting the oilsands would someday have to be phased out, a new study says reducing oil production is exactly what the country needs to be doing if the world is going to meet its targets under the Paris climate agreement.

“Canada’s exports of fossil fuels do not need to drop to zero immediately, but we cannot pursue policies that further increase extracted carbon,” economist Marc Lee wrote in the report for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Parkland Institute.

The report also says that a "major shortcoming" in the Paris climate accord has created an incentive for Canada to extract as much oil as quickly as it can.

![justin trudeau calgary stampede]()

Liberal leader Justin Trudeau attends the Calgary Stampede parade, Friday, July 4, 2014. (Photo: The Canadian Press/Jeff McIntosh)

Under the agreement that Trudeau signed last year, countries measure their progress in reducing emissions by looking at "territorial emissions" — in Canada's case, the carbon that's burned on Canadian soil. But it doesn't include carbon extracted in Canada and sent abroad, in the form of oil or natural gas.

Because Canada extracts much more oil than it burns (about twice as much at this point), it can export oil without taking a hit to its carbon emissions numbers — in essence, the emissions become the importer’s problem. But those importers will soon be looking to cut their own consumption of fossil fuels.

"Therefore, countries like Canada have a powerful incentive to extract fossil fuels now before their value evaporates," the CCPA said in an email. "This ‘green paradox’ is bad news for the climate."

Many industry leaders and policymakers in Canada have argued against measuring the emissions of oil for export at the source, as the CCPA study does.

They argue smaller oil exporting countries like Canada would be unfairly burdened with reductions in emissions on behalf of energy consumers elsewhere.

But the CCPA study argues that "demand-side" policies, like the carbon tax Trudeau introduced, won't be enough to meet the temperature targets in the Paris climate deal. Governments need to implement "supply-side policies to keep carbon in the ground."

Many climate scientists have pointed out that keeping a cap on global temperature growth will require keeping some existing oil reserves in the ground.

"This means a planned, gradual wind-down of these industries needs to begin immediately, rather than the continued pursuit of new fossil fuel infrastructure," the study says.

![donald trump]()

President Donald Trump speaks before signing an executive order in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, DC, on January 24, 2017. Trump signed executive orders reviving the construction of two controversial oil pipelines, but said the projects would be subject to renegotiation. (Photo: Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images)

The CCPA report landed a day after President Donald Trump signed an executive order moving the Keystone XL pipeline forward — though to what extent is unclear. Trump said he wants to "renegotiate" the project, to ensure — among other things — that the pipeline is built with U.S.-made steel.

It also comes a day after Trudeau appeared to backtrack on a comment earlier this month that the oilsands would eventually need to be "phased out."

The Prime Minister's Office initially defended the comment, pointing out that former Prime Minister Stephen Harper said much the same thing. On Tuesday Trudeau said he "misspoke" by making the comment — but then went on to give a long defence of why he believes the oilsands will be phased out.

No change in future expectations after Paris deal

The Paris deal didn’t set out specific emissions reductions for each country, but rather set a goal of keeping temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

What that means is that the deal creates a “carbon budget” for the world — a total amount of carbon that can be burned if global warming is to be kept under that 2 C limit.

No matter how that carbon budget for Canada ends up being calculated, it’s “much smaller than Canada’s proven reserves of fossil fuels,” economist Marc Lee wrote in the report.

![carbon emissions canada]()

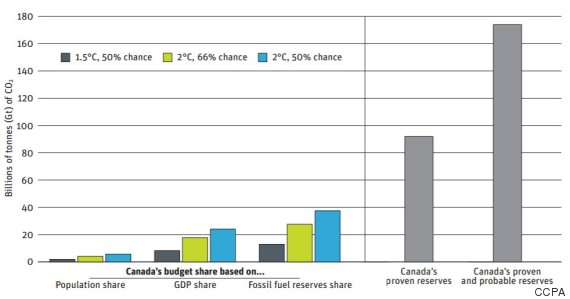

Under any scenario in which the world keeps to its temperature targets under the Paris deal, Canada can only extract a fraction of its fossil fuel reserves, economist Marc Lee writes. (Chart: CCPA)

“The ... carbon budget implies that Canada could extract carbon at current levels for at most between 11 and 24 years."

The CCPA report suggests that the Trudeau government hasn’t taken the first steps necessary to plan for a reduction or phase-out of fossil fuels.

“Neither industry nor government appear to be considering the Paris agreement in their future planning exercises,” Lee wrote. “In spite of the agreement, the National Energy Board continues to forecast increases in Canadian fossil fuel production and exports.”

“Canada’s exports of fossil fuels do not need to drop to zero immediately, but we cannot pursue policies that further increase extracted carbon,” economist Marc Lee wrote in the report for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Parkland Institute.

The report also says that a "major shortcoming" in the Paris climate accord has created an incentive for Canada to extract as much oil as quickly as it can.

Liberal leader Justin Trudeau attends the Calgary Stampede parade, Friday, July 4, 2014. (Photo: The Canadian Press/Jeff McIntosh)

Under the agreement that Trudeau signed last year, countries measure their progress in reducing emissions by looking at "territorial emissions" — in Canada's case, the carbon that's burned on Canadian soil. But it doesn't include carbon extracted in Canada and sent abroad, in the form of oil or natural gas.

Because Canada extracts much more oil than it burns (about twice as much at this point), it can export oil without taking a hit to its carbon emissions numbers — in essence, the emissions become the importer’s problem. But those importers will soon be looking to cut their own consumption of fossil fuels.

"Therefore, countries like Canada have a powerful incentive to extract fossil fuels now before their value evaporates," the CCPA said in an email. "This ‘green paradox’ is bad news for the climate."

“Neither industry nor government appear to be considering the Paris agreement in their future planning exercises."

— Marc Lee, senior economist, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Many industry leaders and policymakers in Canada have argued against measuring the emissions of oil for export at the source, as the CCPA study does.

They argue smaller oil exporting countries like Canada would be unfairly burdened with reductions in emissions on behalf of energy consumers elsewhere.

But the CCPA study argues that "demand-side" policies, like the carbon tax Trudeau introduced, won't be enough to meet the temperature targets in the Paris climate deal. Governments need to implement "supply-side policies to keep carbon in the ground."

Many climate scientists have pointed out that keeping a cap on global temperature growth will require keeping some existing oil reserves in the ground.

"This means a planned, gradual wind-down of these industries needs to begin immediately, rather than the continued pursuit of new fossil fuel infrastructure," the study says.

President Donald Trump speaks before signing an executive order in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, DC, on January 24, 2017. Trump signed executive orders reviving the construction of two controversial oil pipelines, but said the projects would be subject to renegotiation. (Photo: Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images)

The CCPA report landed a day after President Donald Trump signed an executive order moving the Keystone XL pipeline forward — though to what extent is unclear. Trump said he wants to "renegotiate" the project, to ensure — among other things — that the pipeline is built with U.S.-made steel.

It also comes a day after Trudeau appeared to backtrack on a comment earlier this month that the oilsands would eventually need to be "phased out."

The Prime Minister's Office initially defended the comment, pointing out that former Prime Minister Stephen Harper said much the same thing. On Tuesday Trudeau said he "misspoke" by making the comment — but then went on to give a long defence of why he believes the oilsands will be phased out.

No change in future expectations after Paris deal

The Paris deal didn’t set out specific emissions reductions for each country, but rather set a goal of keeping temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

What that means is that the deal creates a “carbon budget” for the world — a total amount of carbon that can be burned if global warming is to be kept under that 2 C limit.

No matter how that carbon budget for Canada ends up being calculated, it’s “much smaller than Canada’s proven reserves of fossil fuels,” economist Marc Lee wrote in the report.

Under any scenario in which the world keeps to its temperature targets under the Paris deal, Canada can only extract a fraction of its fossil fuel reserves, economist Marc Lee writes. (Chart: CCPA)

“The ... carbon budget implies that Canada could extract carbon at current levels for at most between 11 and 24 years."

The CCPA report suggests that the Trudeau government hasn’t taken the first steps necessary to plan for a reduction or phase-out of fossil fuels.

“Neither industry nor government appear to be considering the Paris agreement in their future planning exercises,” Lee wrote. “In spite of the agreement, the National Energy Board continues to forecast increases in Canadian fossil fuel production and exports.”

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.